A Story of Lightbulbs and Lawmakers

— or why we’ll never be prepared for AI.

Created May 19, 2020 - Last updated: May 19, 2020

Here’s a challenge: Make your car disappear in plain sight. Disassemble it down to its individual parts, then hide the pieces behind nearby bushes. I doubt you’d be able to, unless you’re a very savvy car mechanic or perhaps David Copperfield. And why on Earth would you want to do this anyway?

Well, if it wasn’t for Daniel H. Hastings, the governor of the state of Pennsylvania in 1896, then this procedure would have become the law for all drivers of horseless carriages. Hastings vetoed the bill, which unanimously passed both houses and which would have required drivers “upon chance encounters with cattle or livestock to (1) immediately stop the vehicle, (2) immediately and as rapidly as possible … disassemble the automobile, and (3) conceal the various components out of sight, behind nearby bushes until equestrian or livestock is sufficiently pacified.”

These types of laws, known as “Red Flag Laws” were commonplace in other countries around that time. In 1861 and 1865, the United Kingdom introduced a series of laws called the Locomotive Acts, restricting the speed of horseless vehicles to 2mph (3.2km/h) in cities and 4mph (6.4km/h) in the country, and requiring a person with a red flag to walk in front of the vehicle as a warning to other carriages, riders and pedestrians. It took more than 30 years until the red flag requirement was removed and the speed limit increased to 14mph (23km/h).

It sounds ridiculous today, but these laws serve as a good example of how technology is always one step ahead in the cat and mouse game and how wrong we can be when trying to predict the effect new technology has on our lives, or livestock.

Laws have always been subject to change. In order to pass the test of time, they need to be able to adapt to socioeconomic or technological change. Take the United States for example, founded on The Constitution. Article V specifically describes the process of making changes to it, the aptly named Amendments. So far, the constitution has received 27 amendments alone and even those are subject to further change. The 18th amendment for example introduced prohibition in 1919, the ban of alcohol nation-wide, only to be rescinded again 13 years later by the 21st amendment.

The Framers could not have foreseen the kinds of new threats and challenges that the country would face more than 200 years later. But they understood that the world does not stand still, and that geopolitical change and technological progress was inevitable. They created a dynamic system of rules, one that can modify itself, and therefore should have been adequately equipped to react to any future challenges. I say ‘should have’, because it seems we have reached a tipping point where the system can no longer keep up. Let me explain!

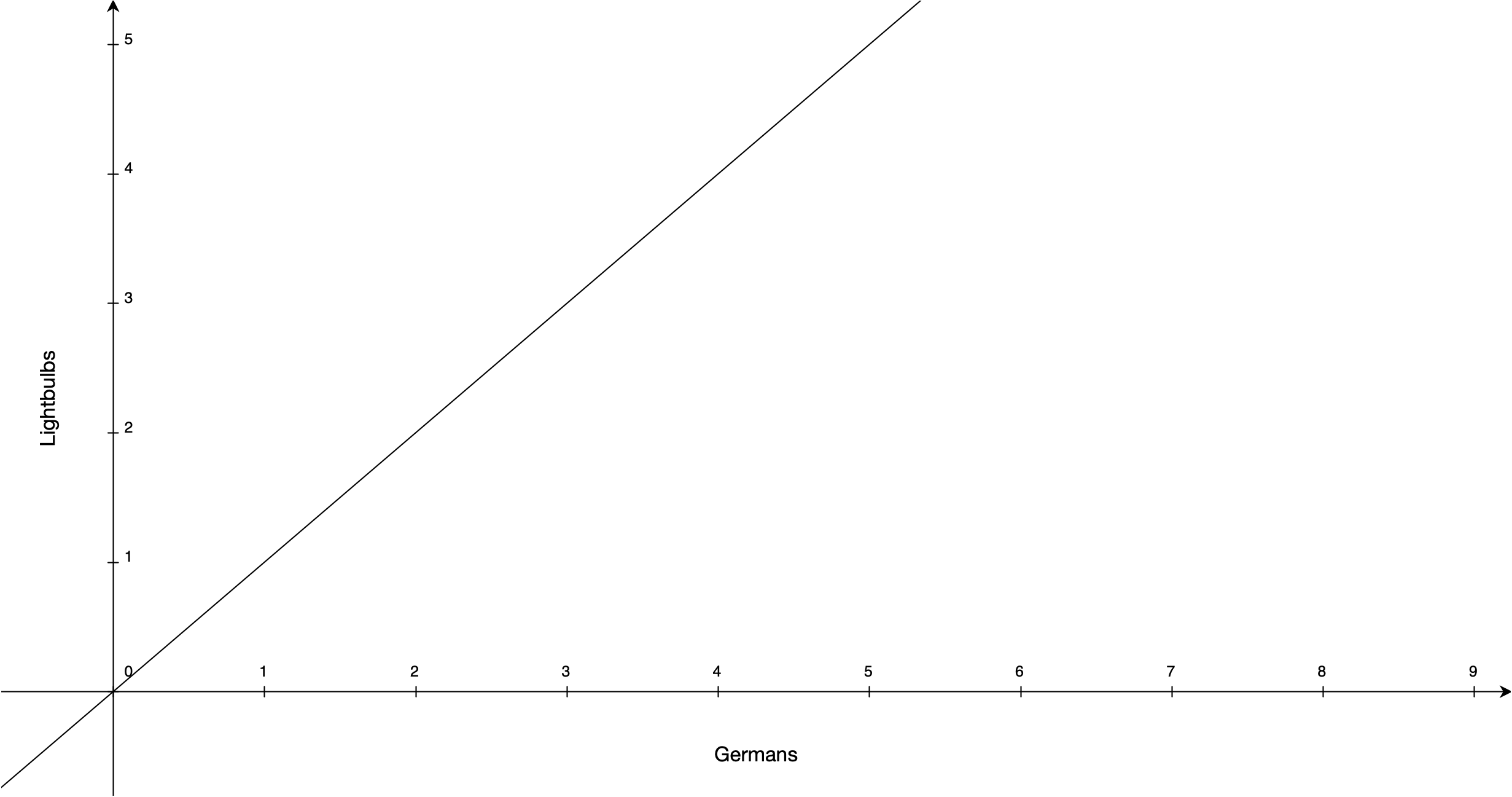

How many Germans does it take to change a light bulb?

The correct answer to this joke is: “One, they are efficient and don’t have a sense of humour”. Being German myself, I never understood why this is funny, but the math makes sense. One German, one light bulb, ten Germans, ten light bulbs, 100 Germans, … you get the idea. This kind of relationship is called linear or proportional growth. The more Germans, the more light bulbs can be changed in the same amount of time.

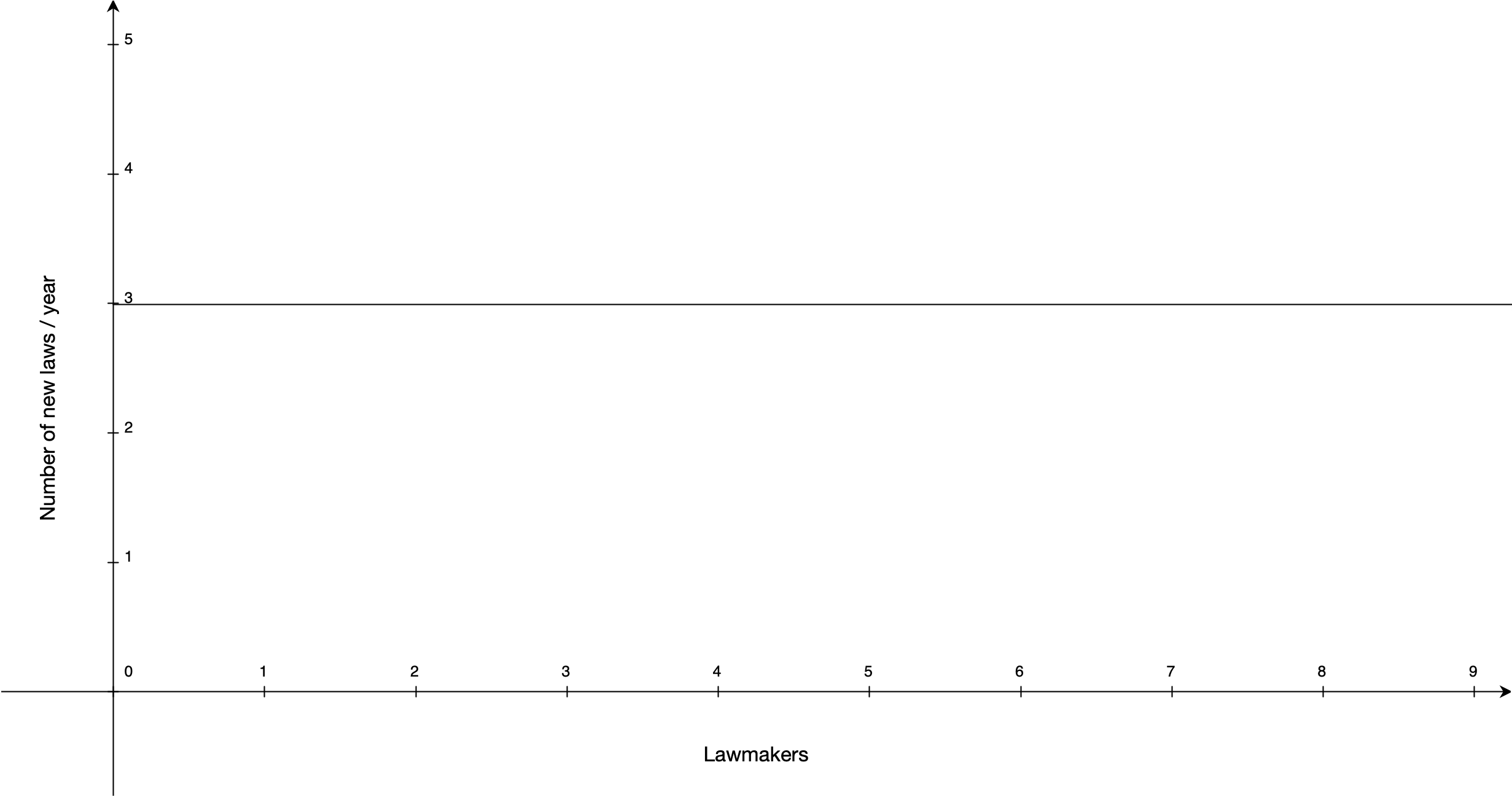

The same is not true for lawmakers. Doubling the number of politicians does not give us twice the amount of laws, or twice the changes to existing laws. Most of us live in representative democracies and the bottleneck of making changes to the law is not the amount of politicians, but the process itself. Any potential new threat to society has to be first noticed, then evaluated, a response has to be formulated, modelled for its efficacy and safety and then introduced as a bill. What follows next is a lengthy and uncertain process through legislature before the bill can be enacted into law. Even under perfect circumstances (namely not hyper-partisan politics or late stage capitalism), this process can take months or sometimes years.

Even worse, as societies grow, their laws and processes tend to get more complex, their politics more partisan, and their ability to react to change gets slower. The best we can hope for is that the time to change the laws remains constant, expressed as a horizontal line in a chart. By the way, it doesn’t matter where that line sits, at 3 (as in the chart below), 30 or 300. The fact remains that it doesn’t increase as the population grows.

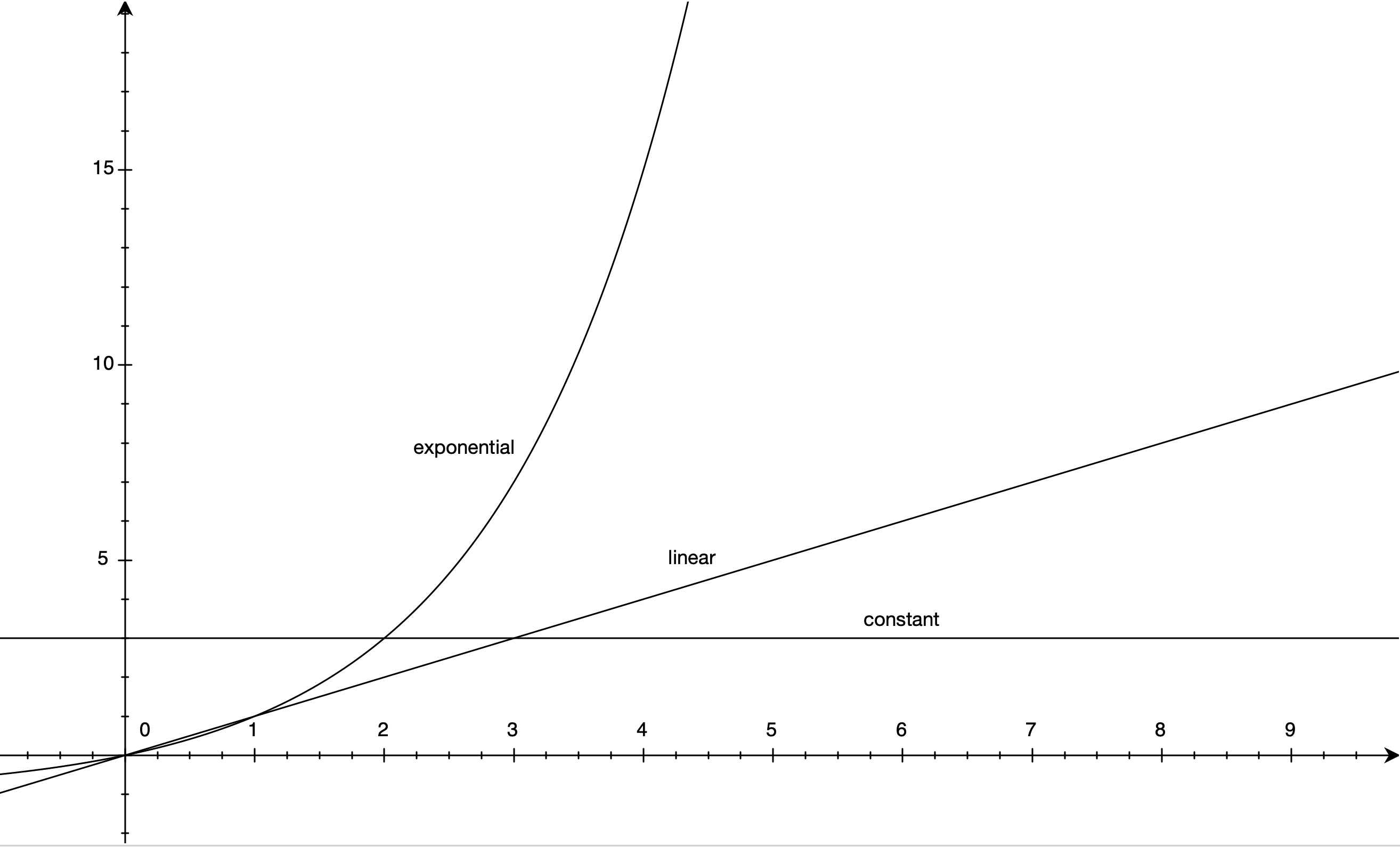

Finally, let’s take a look at exponential growth. Exponential growth can be found everywhere in nature, but it’s surprisingly hard to understand for us humans. What it means is that not the change, but the rate of change grows proportionally over time. In other words, the numbers double in constant intervals. Interest grows exponentially, and so do viruses. Recent events caused by the global COVID-19 outbreak give us a horrific glimpse of what exponential growth feels like: It’s far away and doesn’t affect you, until it suddenly does! In March my company had scheduled a trial work-from-home day for the entire office a week out. That test never happened; the policy had changed so quickly that a few days before said trial, all employees were advised that they would have to work from home immediately and until further notice. Cancer grows exponentially, too. If you’ve ever lost a family member or a friend to cancer, you may better understand what it’s like. Everything was fine, until they get a diagnosis. At this point, they often only have months or even weeks left.

Technological progress, the very thing we determined is one of the main reasons for laws to change, advances exponentially too. You’ve probably heard of Moore’s Law, which is often mistaken as describing the exponential growth of computing power, but more accurately describes the exponential growth of numbers of transistors on a microchip. The two are not the same, although highly correlated. In addition to ever denser computer chips, we have exponential growth in processor clock rates, increase in instruction-level parallelism, more computers being built every year and not to forget the exponential growth of the world population itself: more bright minds advancing the state-of-the-art in technology every day.

One particular field of technology that also advances exponentially, is Artificial Intelligence, or as the science community more modestly calls it, Machine Learning.

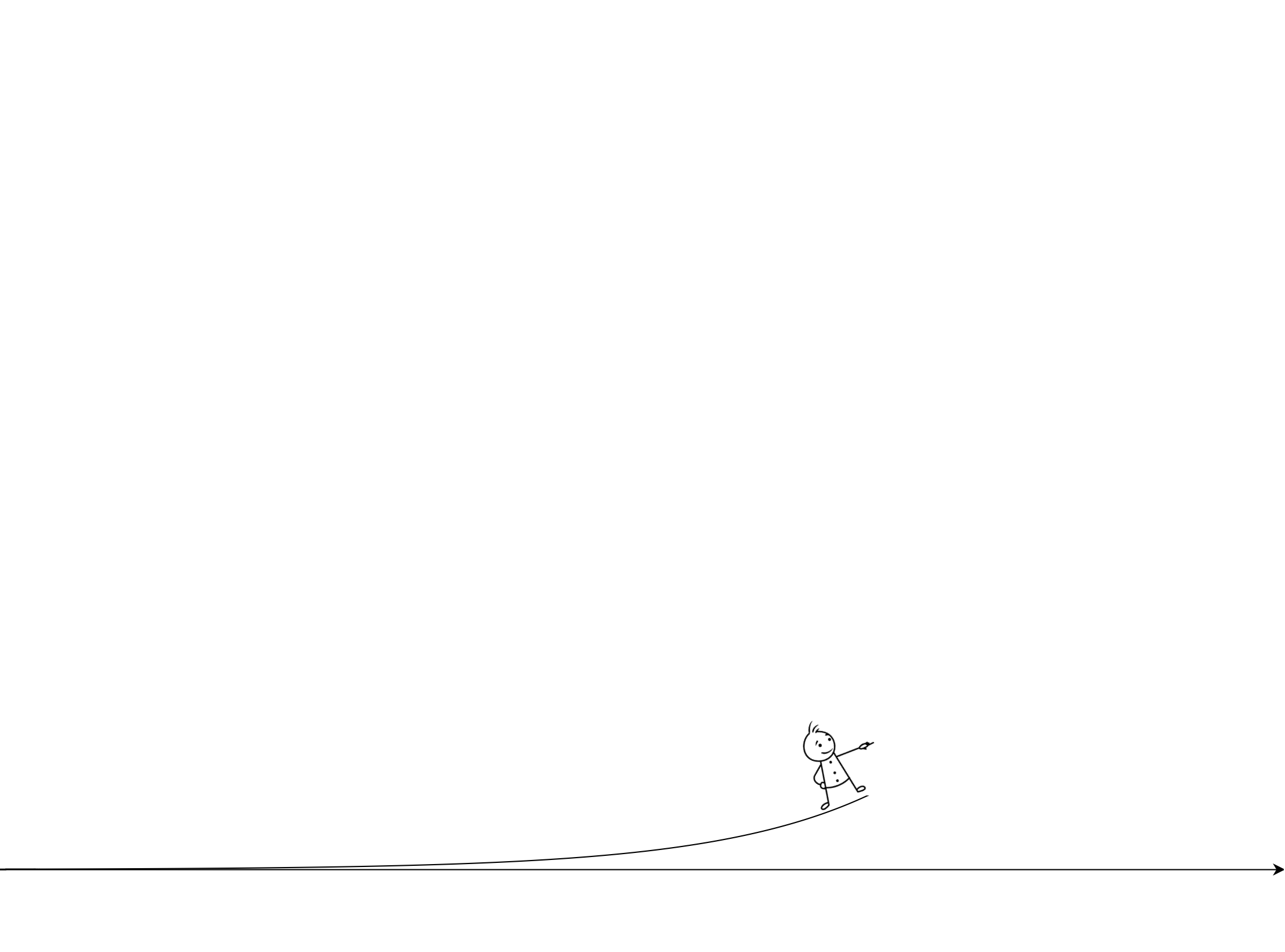

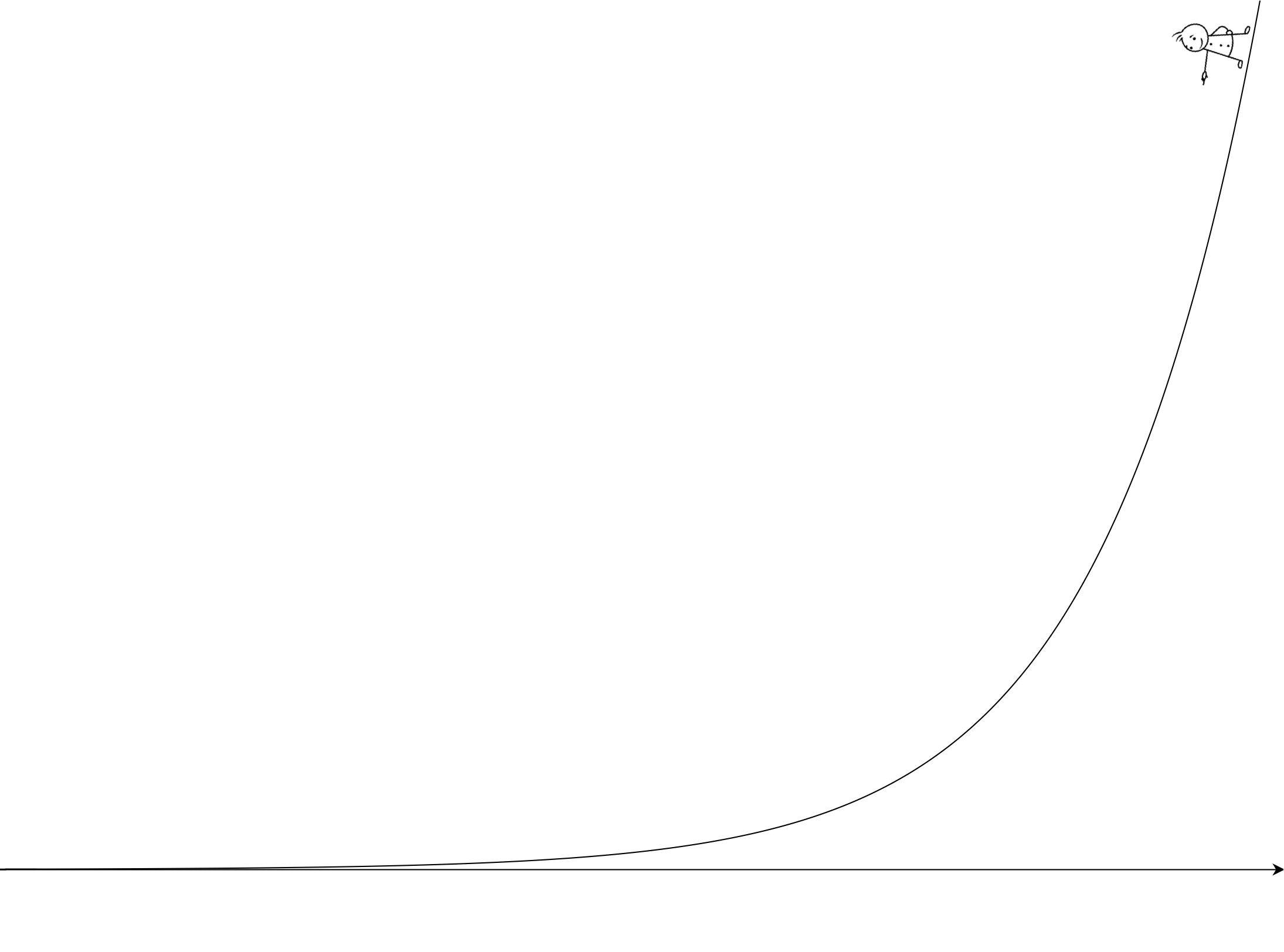

Tim Urban, one of my favourite bloggers, wrote a two-part article about The AI Revolution which I cannot recommend highly enough. He starts by explaining what it feels like to stand at the cliff of an exponential growth curve, looking forwards. This image stuck with me ever since I first read his post, and I’m going to steal the example for your benefit as well (I hope you don’t mind, Tim).

Just looking at this first illustration without seeing the future, you wouldn’t be able to tell that you’d run out of vertical space before reaching the end of the graph. The second illustration has the exact same slope, but is extrapolated just a little further on the x-axis. It’s easy to say after the fact “yep, that was exponential growth”, but looking forward into the unknown, we often can’t distinguish it from linear change, or in the early case from the steady state, no change at all.

As someone with a PhD in Machine Learning, the recent advances in the field scare me profoundly. We can downplay the progress all we want. First it was chess that was touted the holy grail of human intelligence, and AI came for it. Then, a computer unexpectedly, and 10 years early, beat us at Go. While AlphaGo did receive some press coverage and the respect of the ML community, the general population kind of brushed it off as an interesting outlier in our predictions of where AI would be at the time. Now we have humanoid robots doing gymnastics or Parkour and algorithms that write music, poems, or whatever you want.

Many researchers in the field of Machine Learning will remind us that this is narrow AI we’re talking about, one that is good at any one task, but terrible at generalising to other tasks. And they are right. We are still not close to AGI, or Artificial General Intelligence, that can learn anything, and transfer its knowledge to other tasks, like humans can. But Deep Learning, a new strategy of learning algorithms to train deep neural networks, finally seems to get us close to human brain performance. Coincidentally, computing power is estimated to reach the level of human brains in this decade as well. Already, we can generate deep-fake images, sounds and videos that a human can no longer distinguish from reality. Head over to thispersondoesnotexist.com and see for yourself if you recognise anyone (spoiler: you won’t, these images are all computer-generated faces of non-existing people).

If all this is possible today, a mere 82 years after the creation of the first programmable computer Z1 by German Konrad Zuse, and with progress advancing exponentially, where does this leave us in 30 years from now? Or in just 10?

We are all sick and tired of exponential graphs and calls to Flatten the Curve, but it’s the same problem. An exponential force (the virus) hits a constant response (the capacity of a healthcare system). Healthcare systems were never built to deal with that kind of flood of patients. And neither is our legal system ready for the AI tidal wave that’s closing in on us.

We can already see the first symptoms. Tech Giants like Google and Facebook collect every bit of data of their users and run it through ML algorithms, selling highly targeted advertising to the highest bidders, and making billions of dollars every year in the process. In 2015, Facebook has publicly admitted to experimenting on 700,000 unknowing users, and found that they can affect people’s mood by manipulating the content of their feeds. This was half a decade ago, an eternity on the exponential scale. Where are the laws that protect us from those kinds of experiments in the future? That prevent companies from selling our emotional state to advertisers and political parties? Where are the laws that protect us from AI-generated, highly addictive flavours in our drinks, from phones reading our thoughts or analysing our DNA to identify every weakness to be exploited for advertising?

It is no coincidence that the big tech companies all invest heavily in Machine Learning. As Vladimir Putin put it in 2017: “Whoever will lead AI will rule the world.” I believe that he is absolutely right, and that we are already on a downwards spiral towards a winner-takes-all end game: The AI Singularity.